Neuroscience, at its core, is humankind’s effort in answering the seemingly simple question of “How does the brain work?” However, as soon as one begins to carefully poke at this question a bit more, it seems as though an endless supply of other questions begin to fall out.

What causes the brain to not work correctly? How do we make it work correctly?

How many parts of the brain are there? What makes these parts different? How do these parts lead to the behaviors we see in living things?

How do these parts relate to the things in my own experience, like anger, sorrow, or excitement? As a matter of fact, how do all of these pieces of matter result in me being able to experience what it is to be alive?

If these pieces are all just chunks of matter, where does my ability to make my own decisions fit into this picture? How do other organisms also size up? What do they experience?

In a sense, by only asking that first basic question, neuroscience is also looking for answers for each of these as well – understanding the bases of behavior and phenotyping neural diseases, which will hopefully lead to cures; learning how cellular and network functions lead to emergent properties including cognition, and, maybe the most central subject of human experience – experience itself, or consciousness; the free will/determinism debate; and questions of morality related to the treatment of humans and other organisms.

Some of these inquiries, especially the latter few, may sound to you like dreamy thought experiments at best, and indeed many serious scientists consider them to only have a place within the realm of philosophy. Of course, many of the questions neuroscience has begun to chip away at began as philosophical speculation as well – as it seems we have so far to go, it’s difficult to know where a safe place to draw the line really is.

In a nutshell, the field of neuroscience provides us with an important target to aim at. Not only is the target itself significant, but the path that will lead us to it will certainly uncover a plethora of answers to fundamental and consequential questions that color our day-to-day experience. Whatever objective truths we eventually arrive at, they are sure to play a critical role in society’s aim to secure a better future, no matter what that future may ultimately look like. Few other scientific areas (save for, perhaps, machine learning) are likely to have as far-reaching and broad an impact as neuroscience in the coming decades, in part due to developments in technology – as is often the case for revolutions in science.

Before we dive into the details of where we might be going next, however, it will be useful to understand how we reached our current view of the brain so that we may better understand a possible mindset for the future.

A Brief History of Neuroscience

Check out Yuval Noah Harari's "Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind"

Our conception of the brain has only resembled our modern day understanding for a relatively short period of time. We can look to the pantheon of beliefs developed in Ancient Greece as roughly the beginning of any formal attempts to describe the mind. However, theories of the mind and soul ranged quite broadly among different thinkers. Alcmaeon of Croton was perhaps the first to consider the brain as the source for human consciousness, sensation, and knowledge in the 6th century BCE. The famous physician Hippocrates outlined several characteristics of the brain, including how injuries to it resulted in a number of disorders including epilepsy and paralysis [1]. There were, however, many contemporaries to the view that the brain was the organ where such components of the mind were seated, many of whom alternatively held a “cardiocentric” view – that is, that the mind of man is seated within the heart. Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BCE, famously claimed that the brain, being the coldest organ, instead played a role in reducing the heat produced by the heart [2]. Further muddying things, many Greek philosophers believed the “soul” of man to be distributed across the body in different manners. Plato believed there were three components of the soul, including the “immortal” and “divine” logos found within the head, which corresponded to rationality; the root of emotions, known as the thymos, seated in the chest near the heart and lungs; and the epithymētikon, related to craving and sensations, positioned near the diaphragm and liver [3]. Democritus instead believed two souls existed: a rational soul positioned either in the brain or chest, and an irrational soul which was spread across the entire body. The list of ontologies developed by different Greek philosophers, sometimes considering the mind and soul as synonymous and sometimes opposing any connection whatsoever, goes on extensively.

Much more can – and has – been said about the history of studying and reasoning about the human mind, but for brevity’s sake it should suffice to say that any attempts towards understanding it have largely remained garbled speculation until relatively recently. This should come as no surprise, as few concrete methodologies for studying the brain existed before the 20th century; Hippocrates’ rigorous experimentation can very well be considered an outlier when superimposed with the remainder of history, although other small pockets of physiological studies have provided early glances into neuroanatomy [4].

As a side note, however, it should be mentioned that many of the blurry intuitions borne out of rational characterizations of the mind by Greek philosophers have persisted upon experimentation. The differentiation of various mental faculties, although coarse at the time of conception by Plato and other philosophers, is now common knowledge and a pillar of neuroscientific study to this day. Furthermore, we now regard the peripheral nervous system as the continuation of the brain throughout the body, allowing it to facilitate communication and regulate various functions, with a large percentage of its circuits being located within the heart [5]. Recent findings have also shown that the gut contains a largely independent nervous system which communicates important information along the gut-brain axis to the brain [6]. The discrepancy of many features of this system with respect to its central counterpart upstairs indicates at the very least that a distinction should be made between both systems, and that this network might have even evolved prior to the brain [7]. Discoveries like these show that the intuitions of ancient Greeks and many others bore shocking similarities to some of the notions we now accept within our modern pantheon of scientific beliefs. We may want to draw the conclusion that intuition can often bear out upon inspection using the rigor of the scientific method, and that it may be valuable to hone those intuitions in order to ask the right questions. The first step of the scientific method, after all, is to generate a hypothesis, so we better be good at it.

Modern Neuroscience

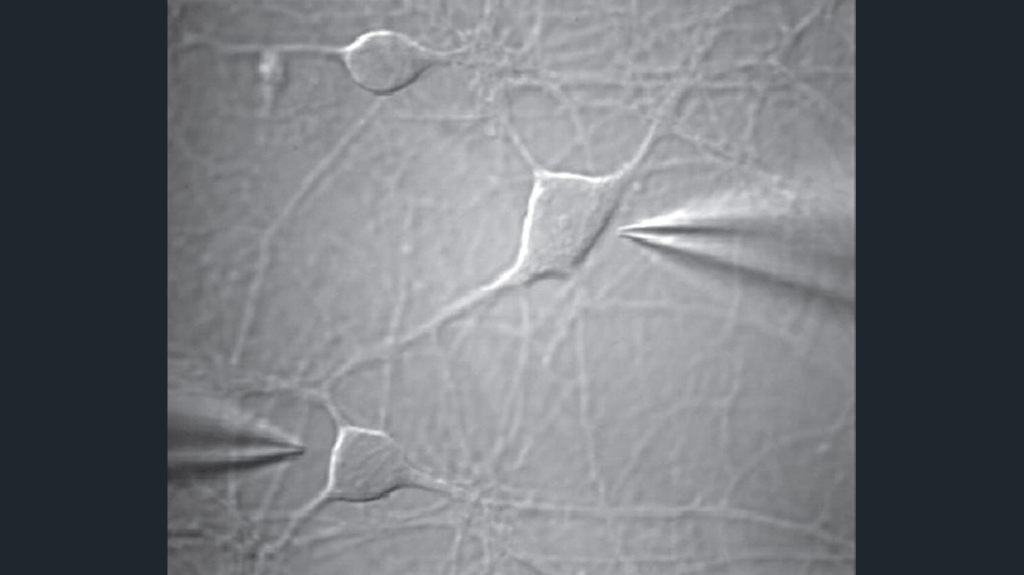

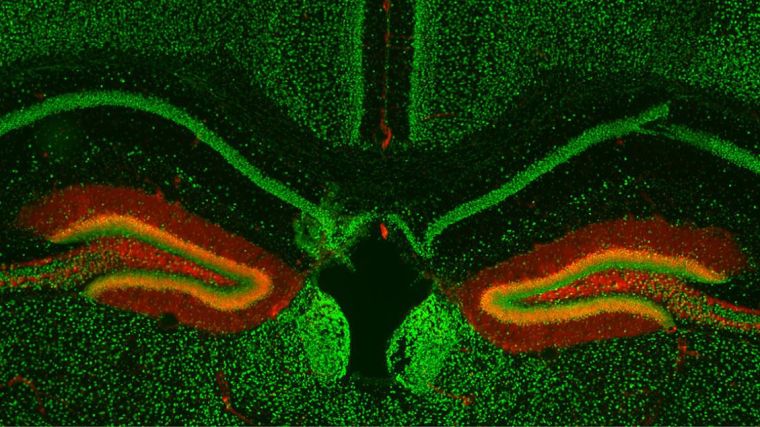

An example of a patch-clamp recording, imaged with electron microscopy (left) and a pharmacological-based experiment on the mouse hippocampus, imaged with fluorescence microscopy (right). Taken from M. Telias and M. Segal [14] and Minichiello Group website, Department of Pharamacology, Oxford University.

Towards the end of the 18th century, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek famously became the first to unveil the realm of cellular biology by pointing microscopes he had developed towards organic matter. Leeuwenhoek himself initially identified axons within nervous tissue [8], and the breakthrough of microscopy led to observations of the somata of neurons as well as the identification of other cells of the brain over the next century. However, the birth of the field of neuroscience is often attributed to Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who in 1888 first revealed the complexity of individual neurons in the central nervous system using an improvement to the Golgi stain [9], which in turn helped to provide evidence for the neuron doctrine [10].

Although the periods leading to and shortly after the introduction of neuroscience were primarily constrained to histology (that is, observing the structure of different tissues using microscopes), the study of cellular mechanisms within individual neurons is still a core aspect of neuroscientific research to this day. Many methods for the examination of neurons are shared with other cells throughout the body – this includes imaging in its many forms, pharmacological studies which can be used to identify the importance and prevalence of molecules in different chemical pathways, and more recent techniques like proteomics and RNA sequencing. A major form of inter- and intra-neuron signaling is by the promulgation of electrical gradients; because of this, a series of experiments such as patch-clamp recordings are also used for studying various electrophysiological properties of neurons. As a more robust understanding of the inner workings of neurons comes to light, greater emphasis is put on determining distinctions between different neuron types. In this sense, much of the work in cellular neuroscientific research is to the end of developing an ontology of cells and determining their characteristics, in terms of their physical properties as well as where they’re found within the brain.

The main alternative to studying high-resolution details at the smallest scale of individual neurons is to instead observe the opposite extreme: the brain in its entirety. Neuroanatomy played a large role in laying the groundwork for a map of the brain. However, studies using non-invasive imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, which tracks temporal changes in blood flow across the brain, and positron emission tomography, which can measure shifts in a number of processes related to metabolism, now dominate studies of neural systems. These methods can determine what areas of the brain become active when a subject is provided a particular stimulus or told to produce some behavior. The details of how these properties arise are still mostly unclear but experiments like these give us insights into what brain regions are responsible for different cognitive functions as well as how the different regions communicate with one another.

It might become clear to see at this point that there is a yawning gap lying between these two primary areas of study. Cellular neuroscience is taking the forest for each individual tree: although this puts us on the path to understanding each individual cell in exquisite detail, all the emergent properties afforded by the complex behavior of these neurons when considered within a network is lost. Stepping all the way back to the scale of the forest misses much of the detail as well – just as a blurry sea of green can’t capture much of the interesting detail that comprises an ecosystem, viewing the output of chemical processes across the brain in low resolution clearly cannot tell us the finer aspects of what is occurring within these systems to produce each component of cognition. As we continue on our quest for a complete picture of the nervous system, it is obvious that another method for observing the brain is necessary.

Recent Advancements: Electron Microscopy and the Machine Learning Revolution

Examples of early electron microscopes compared to modern-day versions. Taken from leo-em.co.uk and cambridgeindependent.co.uk.

Technology has been the primary generator for many of the scientific revolutions across biology, physics, chemistry, and countless other fields throughout history. It may seem like the answer at this point is to wait for some type of imaging technique which can provide us with both cellular-level resolution and brain-level scale. If a non-invasive technique could be developed to accomplish this, that would be incredibly impactful. Unfortunately, this is unlikely to be the case any time soon, as practical computational constraints related to memory and processor capabilities would make this intractable, even if the theory for such a system could be worked out. However, if we are ok with imaging a brain that is no longer living, this technology does, in fact, already exist.

Electron microscopy (EM) has been around for a long time. In fact, its usage in studying maps of nervous systems is not a new concept: in 1986, Sydney Brenner published a complete map of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) [11]. The reason this technique only reached relevance in studying higher-order organisms like humans is twofold. First, the nervous systems of C. elegans contains only 302 neurons in the hermaphroditic adult. Fully developed humans, on the other hand, are estimated to possess somewhere near 100 billion neurons – the difference in scale is simply staggering. Second, Brenner’s map required two decades of effort to complete. This is because EM imaging, when used to investigate 3-D structures, is utilized by generating a stack of 2-D image slices. A brain, for instance, can be cut into extremely thin sheets, and for each sheet, the microscope takes a picture. The neurons in each image can then segmented, and when stacked one on top of the other, the overall shape of the neuron will be reproduced. Going along at the pace-per-neuron that Brenner’s team took would require 6.6 x 109 years to complete a full human brain. Ok, so what if we just get a bit smarter about this and make a huge team of people fully devoted to mapping the brain? Maybe in doing so we could speed up this process by a factor of 100. Unfortunately, this would still require more time than the current age of the universe. Clearly, a significant speed-up is needed.

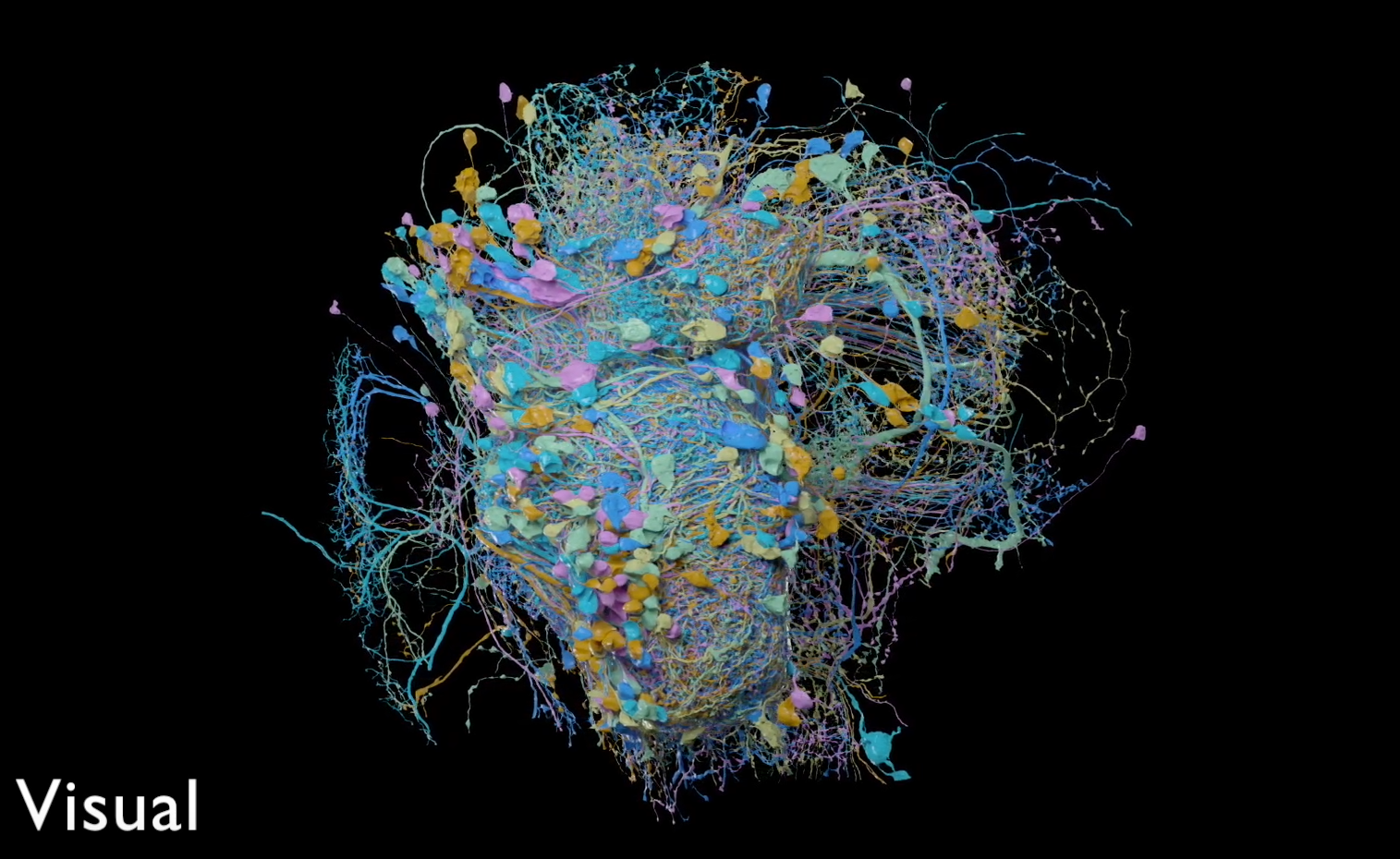

Sample of a partially-reconstructed drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) hemibrain

Fortunately, the field of machine learning has only recently begun its own revolution, sometimes termed the “deep learning revolution,” thanks to concepts gleaned from studying the brain (as well as a few practical requirements like faster processing and greater data availability). In an intriguing twist of reality, machine learning, taking its modern form primarily based on neuroscientific notions, is now proving highly beneficial to furthering knowledge in neuroscience. Possibly the largest impact machine learning has had on neuroscience so far has been to make the task of reconstructing the human brain from EM slices now tractable. Computer vision, a field that studies image and video-related tasks like image classification, instance segmentation, and object tracking, has received a great deal of help from machine learning over the past several years – in fact, recent computer vision research has become nearly synonymous with machine learning. Unsurprisingly, the completion of segmentations for the human brain is almost an ideal machine learning challenge. Once an algorithm has been trained to segment the components of a neuron as well as the other cells found within an EM image, it can then be set free to map out entire volumes at blazing speed when compared to a human. So far, well-funded research groups have been successful in developing a number of 3-D reconstructions – at the time of writing this, nearly a quarter of the neurons within an adult fruit fly brain have been reconstructed using a machine learning segmentation algorithm [12], as have portions of brains from other organisms including humans and the zebra finch [13]. Most of these efforts are being funded by research organizations including the Allen Institute, Janelia, Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology, and Google AI.

Reconstructions provide us with a wealth of information, detailing the structure of networks and providing a holistic view on how the morphology of neurons can vary across the brain. For the first time, we can explore the vast jungle of the brain, journey to its deepest thickets, and return with new insights on how the connective structure may produce certain behavioral outputs. However, a lot of information is still missing when viewing a reconstruction rather than a living, dynamic brain.

Finally, we have arrived at our destination: enter simulation neuroscience.

The Entry of Simulation Neuroscience

Computational modeling has been an important method for studying the brain for a long period of time. Using basic models of individual neurons has helped to ossify a number of experimental results in neuroscience and has already been useful in making predictions that are in turn capable of being verified experimentally. There really isn’t a question about the value of modeling at this point – the only thing left to be asked is how far modeling can take us.

As I stated at the beginning of this essay, the primary objective of neuroscience is to answer the question of “How does the brain work?” At this point, it should be clear that the brain is simply far too complex to be studied on only one scale or another – we need a holistic approach that takes into consideration every detail of the brain at once (or at the very least, every detail of a particular region) if we want to start rigorously understanding each aspect of cognition.

Rich, descriptive computational models may be the best way to synthesize the wealth of information gathered across all areas of research. Recently developed 3-D reconstructions effectively map the neural connections across the entire brain and may also provide a “fingerprint” of each cell which could be used to determine key features about them. Using the cellular ontologies currently being developed in concert with the rich information we now possess regarding cellular function, we can determine the computational properties of individual cells and place these details into our model. Finally, we can utilize functional data received from systems neuroscience research as well as behavioral observations to compare with a model’s outputs and verify its robustness. By building up a high-fidelity model of the brain, this would allow us to observe any number of details and provide access to countless experiments that can’t ethically be reproduced within a human brain. We could remove different components from the model in order to test which features are vital to particular functions and which features are less important.

With a more complete understanding regarding the function of the brain, we could begin to gain insights into so many questions that are yet unanswered. We could break down diseases into their constituent parts, determine what their root causes are, and eradicate them from the human condition. We may produce undeniable evidence that the brain operates deterministically – that free will is, in fact, an illusion – and be forced to internalize objective facts that might lead us to be more humble and forgiving. We may, for the first time, discern the “neural correlates of consciousness” and observe the fundamental components of what comprises conscious experience staring blankly back towards us.

Of course, many of these questions are highly hypothetical, and until we have access to all of the constituent pieces of what makes up a dynamic human brain (remember that we don’t have methods for observing a living human brain for many types of studies), there are likely still questions that won’t be answered from simulations. However, it may very well just be a matter of time until we can, and the fact of the matter is that there is no way to know what we may uncover with our current technology until we start to do the work. Simulation neuroscience is only now beginning to hit its stride, and many groups are working on this task simultaneously. Science is always at its best when multiple people are asking the same question in different ways, and we will certainly get to see many flavors of these simulation models in the coming years. This is an exciting time for both neuroscience and machine learning, as each one is very likely to experience a revolution which will result in a furthering of humankind’s fundamental understanding of itself while also extending its capabilities. I am excited to be in the process of becoming a part of this effort, not only through contribution to scientific discovery, but also by helping to ensure that these discoveries lead to further human flourishing.

— M

P.S. Congratulations on making it to the end! I promise my other posts won’t be this long; I wanted this to serve as a nice overview of neuroscience, but I intend for the majority of my next posts to be readable in 5 minutes or less.

References

[1] E. Crivellato and D. Ribatti, “Soul, mind, brain: Greek philosophy and the birth of neuroscience,” Brain Res. Bull., vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 327–336, Jan. 2007.

[2] C. G. Gross, “Aristotle on the Brain,” Neuroscientist, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 245–250, Jul. 1995.

[3] Plato, Timeus, in: C. Giarratano (Ed.), Platonis Opera, vol. 6, Editori Laterza, Bari, 1971.

[4] Q. Wang, Yi Lin Gai Cuo: Correcting the Errors in the Forest of Medicine. Blue Poppy Enterprises, Inc., 2007.

[5] I. Durães Campos, V. Pinto, N. Sousa, and V. H. Pereira, “A brain within the heart: A review on the intracardiac nervous system,” J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol., vol. 119, pp. 1–9, Jun. 2018.

[6] M. Carabotti, A. Scirocco, M. A. Maselli, and C. Severi, “The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems,” Ann. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 203–209, Apr. 2015.

[7] N. J. Spencer et al., “Long range synchronization within the enteric nervous system underlies propulsion along the large intestine in mice,” Commun Biol, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 955, Aug. 2021.

[8] A. van Leeuwenhoek, Epistolae physiologicae super compluribus naturae arcanis. Apud Adrianum Beman, 1719.

[9] S. Ramón y Cajal, Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves. 1888.

[10] S. Ramón Y Cajal, “Structure and connections of neurons,” Bull. Los Angel. Neuro. Soc., vol. 17, no. 1–2, pp. 5–46, Mar. 1952.

[11] J. G. White, E. Southgate, J. N. Thomson, and S. Brenner, “The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., vol. 314, no. 1165, pp. 1–340, Nov. 1986.

[12] L. K. Scheffer et al., “A connectome and analysis of the adult Drosophila central brain,” eLife, vol. 9, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.7554/eLife.57443.

[13] V. Jain and M. Januszewski, “Improving Connectomics by an Order of Magnitude,” Google AI Blog, Jul. 16, 2018. https://ai.googleblog.com/2018/07/improving-connectomics-by-order-of.html (accessed Feb. 07, 2022).

[14] M. Telias and M. Segal, “Patch-Clamp Recordings from Human Embryonic Stem Cells-Derived Fragile X Neurons,” in Fragile-X Syndrome: Methods and Protocols, D. Ben-Yosef and Y. Mayshar, Eds. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2019, pp. 131–139.

A special thanks to the following resources I used for developing this essay:

X. Fan and H. Markram, “A Brief History of Simulation Neuroscience,” Front. Neuroinform., vol. 13, p. 32, May 2019.

E. Crivellato and D. Ribatti, “Soul, mind, brain: Greek philosophy and the birth of neuroscience,” Brain Res. Bull., vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 327–336, Jan. 2007.

D. Toker, “The Brain Scientist.” Daniel Toker – a Bundle of Thoughts, https://thebrainscientist.com